Every industry needs a mantra. Biotech borrowed “fail fast” from tech and wore it like a badge of progress. It promised courage, iteration, and smarter decisions. But in an environment defined by regulation, patient safety, and timelines that stretch for years, the question isn’t whether we should fail fast. It’s whether we can afford to fail carelessly.

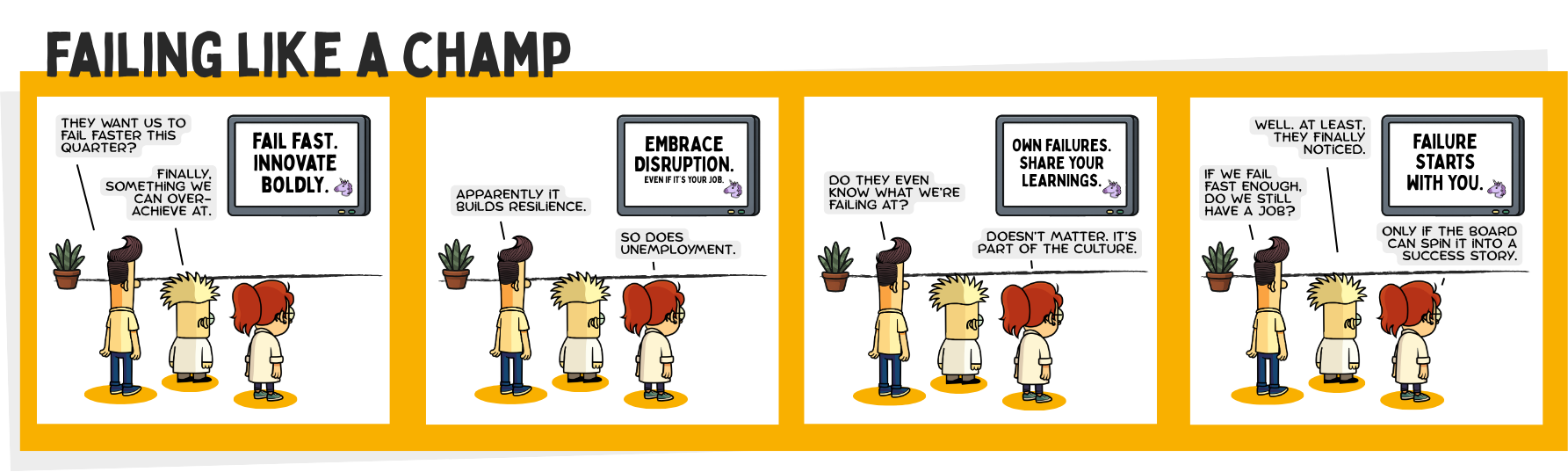

You’ve heard it in meetings, workshops, and town halls. Fail fast. The phrase lands with confidence. It sounds modern. It promises movement. It makes innovation sound like something that can be scheduled.

But you also know how it plays out. A project misses a milestone, the slides are rewritten, and the word “learning” gets a new bullet point. The same system that preaches speed struggles to admit that real discovery is slow, expensive, and often inconvenient. “Fail fast” was supposed to make us braver. Too often, it just made the failure cheaper to explain.

What You Already See

You know that science doesn’t move like software. There’s no quick restart. There’s no “push to production.” The work you do runs on patient data, controlled materials, and audits that don’t forgive experiments gone wrong. Still, the slogans keep coming. Agility. Resilience. Continuous improvement. Words that fill slide decks faster than they ever change outcomes.

If you work in R&D, you’ve watched it happen. A failed study gets reframed as progress. A delay becomes a “strategic pause.” Reports multiply until everyone looks busy and no one remembers what the experiment was meant to test. Somewhere along the way, “failing fast” turned into managing optics.

Science never needed a new mindset for failure. It already had one: hypothesis, data, review, revision. The process wasn’t slow. It was deliberate. What slowed it down was pretending that slogans could replace structure.

What Comes Next

If we’re serious about learning, we need to stop treating failure as a performance metric. That means smaller tests, clearer hypotheses, and the kind of governance that protects curiosity instead of branding it. You don’t need to fail faster. You need to fail in a way that teaches something.

The next phase of innovation won’t come from another workshop or internal campaign. It’ll come from teams that still care more about what the data says than how it looks on a slide.

Progress isn’t fast or slow. It’s honest.