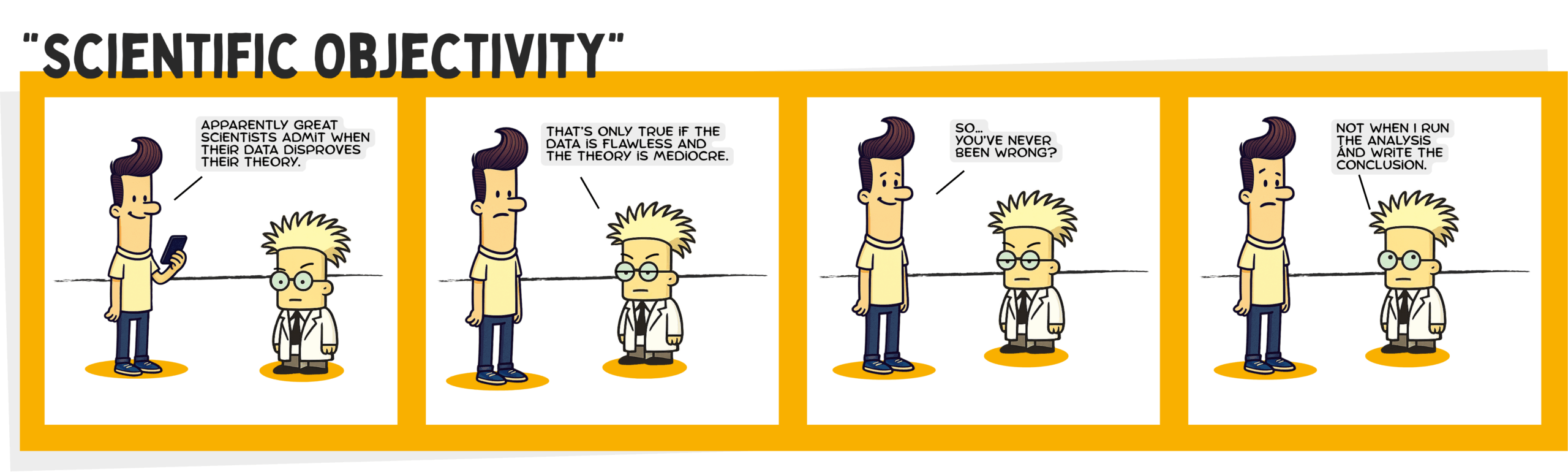

“Apparently great scientists admit when their data disproves their theory.”

That’s the setup in the comic. It sounds noble, even aspirational. But then comes the kicker: “That’s only true if the data is flawless and the theory is mediocre.” And with a perfectly smug punchline: “Not when I run the analysis and write the conclusion.”

It’s funny because it’s true. Uncomfortably true.

The Myth of Neutrality

We like to think science is the ultimate neutral ground. A world where facts win, where personal bias gets left at the lab door, where peer review scrubs away any lingering subjectivity. But in reality, objectivity in science is more ideal than norm. The moment human interpretation enters the picture, bias walks in with it, clipboard in hand.

Bias in the Boring Details

This isn’t just about shady researchers or obviously manipulated data. It’s about the subtle ways in which bias creeps into decisions that feel technical, even boring. What data do you include in your analysis? What do you leave out? Which statistical test do you choose? How do you define “significance”? And perhaps most powerfully, how do you phrase your conclusion so it feels grounded without sounding too uncertain?

Shaping the Truth Without Realizing It

The answers to these questions aren’t purely scientific. They are strategic. And even when intentions are good, the outcome is often shaped by personal conviction, institutional culture, or the simple desire to not look like a fool in front of your peers.

The phrase “not when I run the analysis and write the conclusion” gets a laugh because every scientist knows it carries weight. When you control the method and the message, you shape the truth. You might not even mean to. But if you have a hunch, a favorite hypothesis, or a long-standing belief, your interpretation of the data tends to bend in that direction. Sometimes it’s barely noticeable. Other times, it’s the difference between a breakthrough and a retraction.

The Real Risk: Self-Deception

The real danger is not malicious intent. It’s self-deception. Convincing yourself you’re being objective when you’re actually just being clever. You’ve picked the “most appropriate” methodology that happens to confirm your expectation. You’ve ruled out an outlier that makes your p-value inconvenient. You’ve massaged your language to sound cautiously optimistic, even when the results are screaming “inconclusive.”

This is especially relevant in biotech and pharma, where the pressure to publish, secure funding, or hit milestones is intense. A positive trend, even if borderline, can mean the difference between a Series A and a stalled pipeline. The story you tell with your data isn’t just scientific. It’s commercial.

So Where Does That Leave Us?

First, we should stop pretending objectivity is a binary state. You’re not either objective or not. You’re navigating a spectrum, making choices that influence perception. Acknowledging this doesn’t weaken the scientific process. It strengthens it. It creates space for more rigorous debate, more transparency, and fewer illusions.

Second, we need to train scientists not just in technical skill, but in epistemic humility. The ability to hold their own ideas loosely. To build enough trust in the process that changing your mind is not a failure, but a function of maturity. Objectivity isn’t about having no bias. It’s about being honest about where it might be hiding.

Science Gets Stronger With Honesty

And finally, maybe we should laugh a little more about it. Because sometimes the only way to deal with the gap between how science works and how it’s presented is to point it out, smile, and keep trying to do better.

Not every theory is right. Not every data point is clean. But if we can be transparent about the mess, the science actually gets stronger.

And that’s a conclusion worth writing.